Achieving decarbonization and net-zero goals depends on strategic shifts across all industries. For the transportation of cargo, a shift in the modal mix can deliver huge benefits. Crucial cargo, everything purchased and consumed, is always moving along the supply chain—but it moves greener and more efficiently with a multimodal mix that minimizes the landside portion of that journey and maximizes maritime transportation on the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Seaway System and beyond.

Environmentally-Friendly Waterborne Shipping

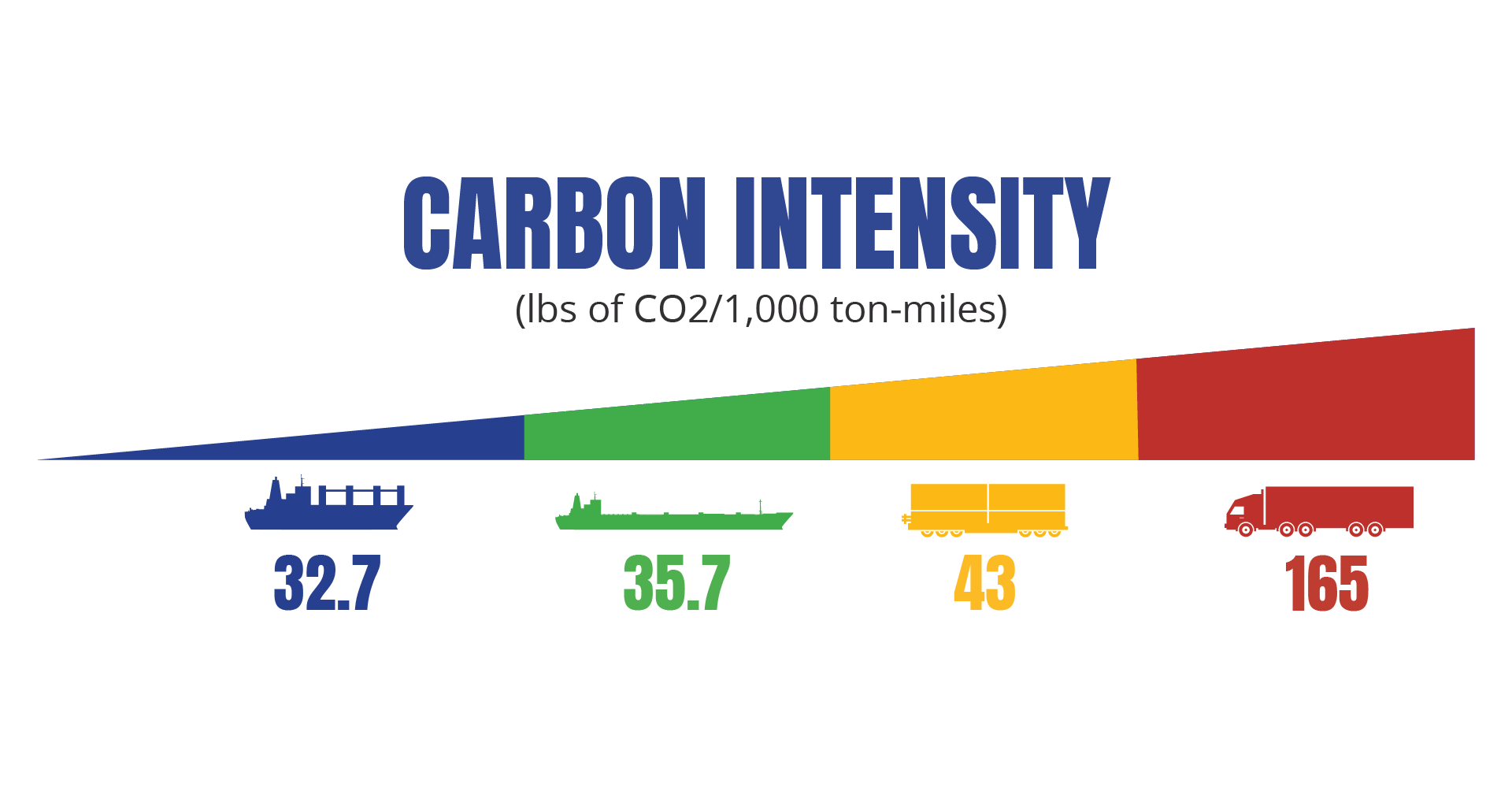

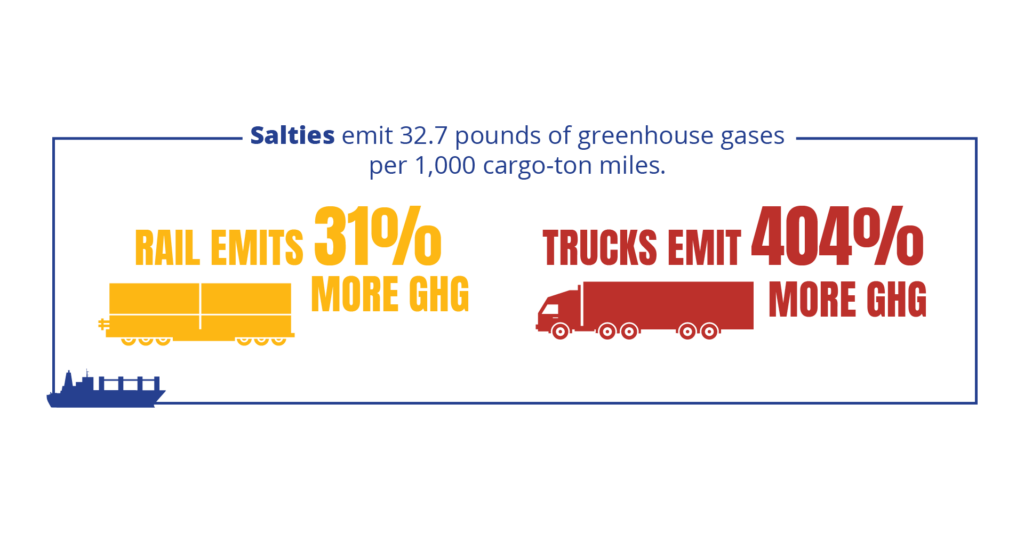

Waterborne shipping is one of the most energy efficient and environmentally friendly ways to move cargo, and when maximized in conjunction with efficient last-mile rail and road transport, it can move goods further, faster, and at lower costs with less carbon intensity.

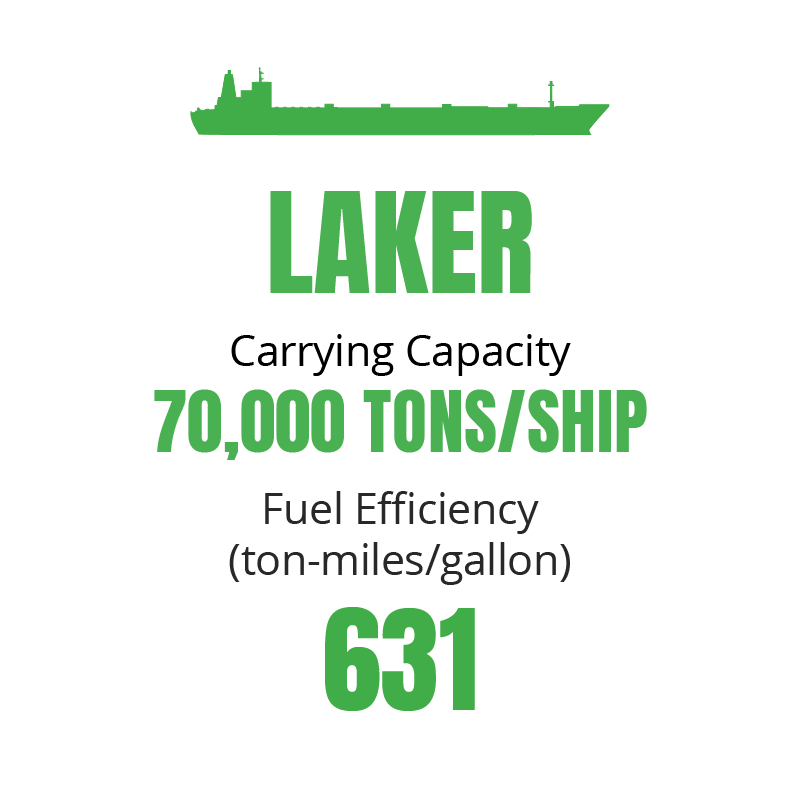

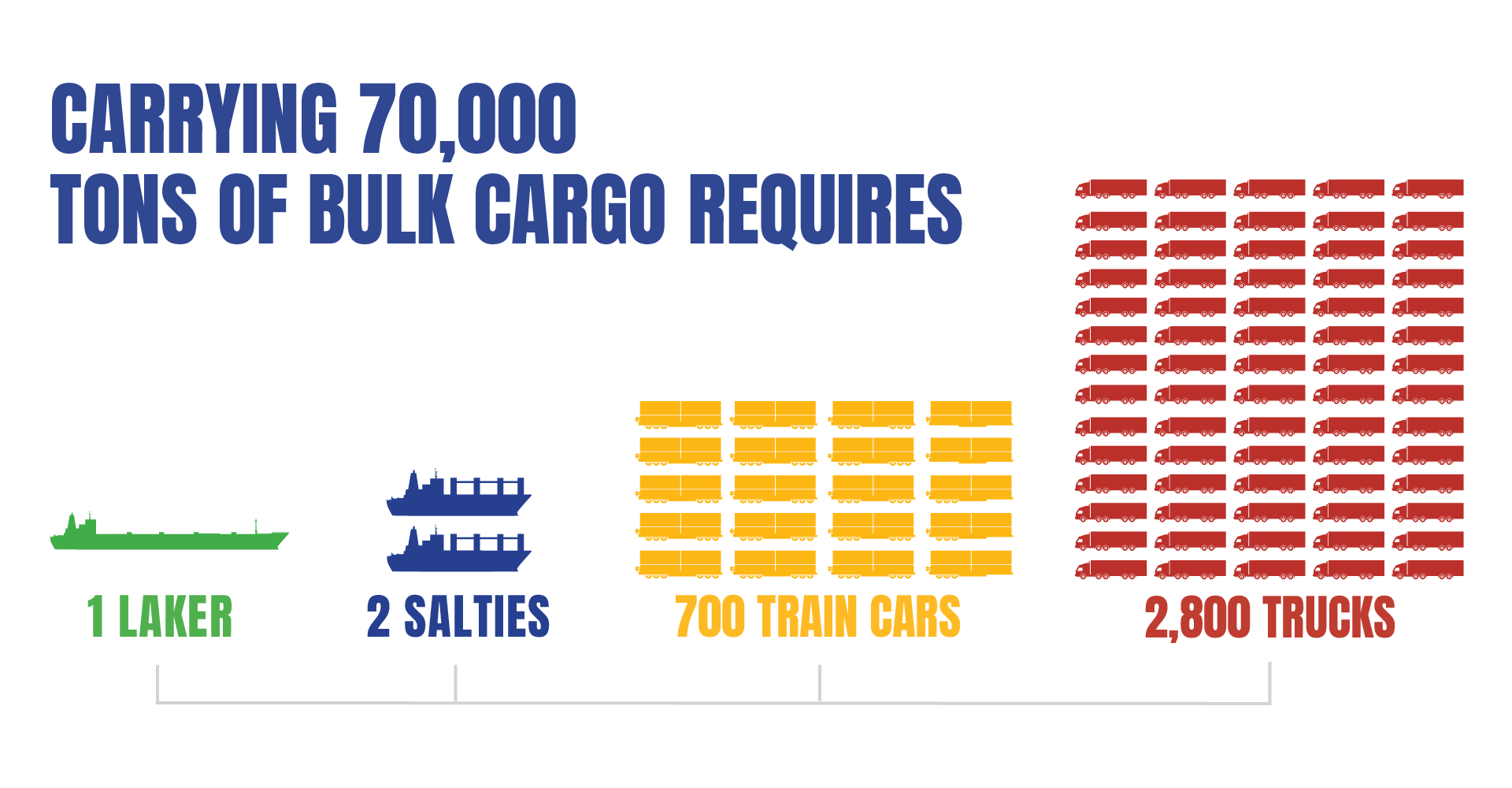

Two types of freighters most commonly sail the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Seaway System: lakers and salties. Both vessel types have an astounding carrying capacity and capability to transport vast quantities of cargo more efficiently than any other mode of transport.

Lakers are very large ships, some over 1,000 feet long, which operate exclusively within the freshwater Great Lakes, transporting bulk raw materials such as iron ore, limestone, salt, stone, fertilizer, and coal. Some also move breakbulk cargoes, like steel, machinery, and containerized goods.

Salties are Seaway-sized ships (up to 740 feet long) that carry bulk cargo (e.g., grain, cement), breakbulk cargo (e.g., heavy-lift cargo, project cargoes, like wind turbine blades) and containerized goods on the Great Lakes and oceans.

Relieving the Pressure

Great Lakes ships transport the equivalent of 11 million truckloads per year, which decreases wear and tear on our nation’s highways, reduces traffic congestion, and reduces fuel consumption. It also alleviates pressure related to the trucking industry’s continued workforce shortage, creating net-positive benefits for the transportation industry and beyond. Imagine the possibilities of even more waterborne shipping!

and 78% compared to trucks.

More Ships >> Less Emissions

Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Seaway commercial navigation generates fewer greenhouse gases because it can transport more cargo with less emissions.

Portside Efficiencies in Duluth-Superior

The Duluth Seaway Port Authority’s Clure Terminal is a multimodal logistics hub that connects road, rail, and maritime cargo transportation to deliver optimal service. The terminal includes six active ship berths, on-dock connections to four Class I railways, seamless highway access, and the CN Duluth Intermodal Terminal, a rail-served intermodal container hub that complements the terminal’s maritime container-handling capabilities.

Whether in or outbound by water, road, or rail, the terminal’s facilities, equipment, and technology handle the largest, most complex cargoes with ease—and it’s continually evolving to operate more efficiently.

Renewable Shore Power

- Sourced from Minnesota Power, which supplies 50% renewable energy

- Reduces ship idling and diesel generator operation

- Reduces marine oil consumption

- Alleviates air pollution

- Supports battery charging infrastructure

Electrification of Equipment and Transport Vehicles

The Port of Duluth-Superior has used electric gantry cranes since the Clure Terminal opened and is currently exploring the viability of electrifying additional lift equipment and vehicles in the port’s fleet, like forklifts.

Duluth Seaway Port Authority Climate Action Plan

In June 2024, the Duluth Seaway Port Authority adopted a climate action plan with a goal of net-zero carbon by 2050.

The best modal balance calls for more waterborne shipping.

Maritime shipping and increased use of inland waterways are essential to any freight strategy focused on creating a more efficient, resilient, and environmentally friendly supply chain. The Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Seaway System has the capacity to double the number of vessels currently plying its waters. It’s time to fully leverage our existing marine infrastructure. A greener and more sustainable future depends on it.

Environmental FAQ

What is Green Marine?

Key stakeholders on the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Seaway System, including the Duluth Seaway Port Authority, formed Green Marine, a voluntary partnership, in 2007 to continually improve the maritime industry’s environmental performance. Green Marine’s ongoing efforts encourage and promote sustainable maritime development along this binational trade corridor and around the world. Partners adopt environmental best practices and evaluate their performance each year in a variety of categories including emissions, greenhouse gases, cargo residues and environmental leadership in an effort to reduce the industry’s collective environmental footprint.

What is being done to control the entry of aquatic non-native species from ballast water into the Great Lakes?

The Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Seaway has the most stringent ballast water management and inspection measures in the world. A joint Canada-U.S. inspection program has been in place since 2006 that inspects all arriving vessels from overseas. Oceangoing vessels must exchange ballast and flush tanks before arriving in domestic waters. Since this program started, no new aquatic invasive species invasions due to shipping have been documented in the Great Lakes region.

Domestically, the Vessel Incidental Discharge Act (VIDA) became law in December 2018. VIDA requires the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to develop new national standards of performance for commercial vessel discharges and the U.S. Coast Guard to develop corresponding implementing regulations. Discharge standards are technology-based and in the form of numeric effluent limits and best management practices; distinguish among classes, types, and sizes of vessels, and between new and existing vessels. The unique bulk cargo vessels operating exclusively within the Great Lakes encounter particularly challenging conditions that prevent typical ballast treatment systems from providing consistently effective treatment. Therefore the EPA is supporting research and development of treatment technologies through the Great Waters Research Collaborative in Superior, WI. For more information on aquatic invasive species, visit the Minnesota Sea Grant website.

What is ballast?

When not fully loaded, cargo ships must take on water (ballast) to maintain stability. Once pumped onboard, ballast water is stored in large confined compartments (ballast tanks) built into the hull of a ship.

What is happening with vessel sulfur emissions and the Emissions Control Area (ECA)?

In 2009, the United States and Canada requested that the International Maritime Organization (IMO) approve an ECA for most waters inside the EEZ. The IMO approved the request and the EPA issued proposed rules prohibiting vessels from purchasing fuel with sulfur content higher than 0.5 percent beginning in 2012 and 0.1 percent beginning in 2015. In 2020, the IMO also set a 0.5 percent limit for ships operating outside designated ECAs.

Current sulfur levels for residual fuels burned in ships’ power plants is about 1.5 percent, compared to a worldwide level of as high as 4.5 percent. Shipping interests recognized a safety and competitive problem with these rules because the ultra-low sulfur fuels are considerably more expensive than the fuels currently burned by most ships (up to 100 percent higher cost).

The Great Lakes were included in the proposed rules, which meant that a ship traveling to Duluth from the North Atlantic will need to burn the ultra-low sulfur diesel fuel for about 2,500 miles both inbound and outbound from Duluth. There is much concern about the competitive implications of this, and many believe it could cause modal shifts away from efficient ships to much less efficient rail and truck shipments to the coasts, as this regulation could add up to $3 per ton to the cost of transporting a cargo out of the system.

For domestic ships, Congress acted to currently exempt the older steamers as well as certain older diesel-powered ships that cannot safely burn the low sulfur fuel or can demonstrate hardship due to new fuel regulations. Many ship owners and their trade and professional organizations are working to find ways to reduce their environmental footprint.